King John, His Barons, and the History of Magna Carta

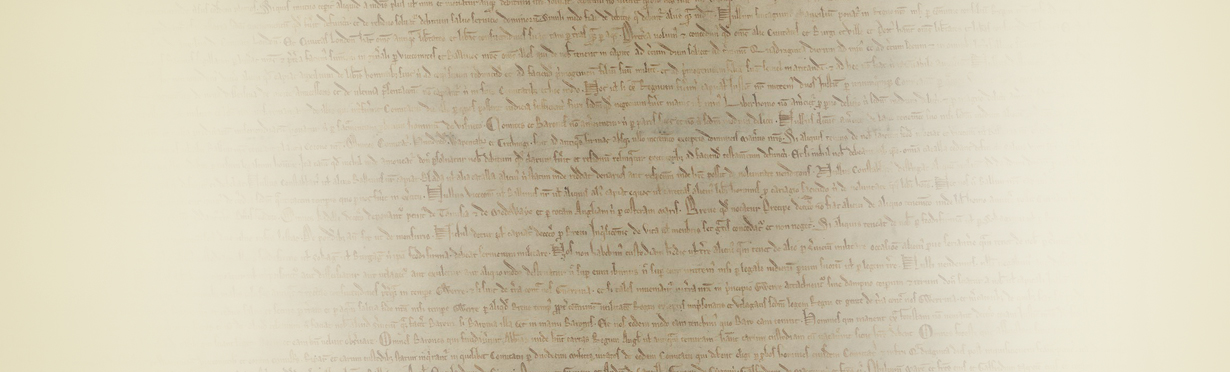

‘The Great Charter’, better known as Magna Carta, is one of the most famous, most significant and most influential documents in the world. The sealing of the Magna Carta by King John in 1215 meant that for the first time in English history every single person in the country – including the king himself – was subject to the law.

This may seem like a rather magnanimous and even noble act for such a ruler to make. But, perhaps unsurprisingly, it was not an act that was undertaken entirely without duress.

Let’s jump back in time to understand the state of the nation when the Magna Carta was first conceived.

Before King John acceded, the English throne was the official seat of King Richard the Lionheart – so called due to his reputation as a great warrior and military leader. Indeed, King Richard’s thirst for battle cost his country a great deal. Fighting wars is not a particularly economical endeavour – especially on foreign soil. The Lionheart in fact spent most of his reign in France and the Middle East where he fought against the Turks who had taken the city of Jerusalem, where it was (and still is) believed that Jesus had died and been buried.

The English were taxed heavily to finance King Richard’s warmongering escapades, and, when he died in 1199, his brother and successor to the throne King John continued to do battle on the continent with the French.

King John

King John, however, was not the brave, knightly warrior that his brother was, and he in fact lost more battles than he won. But in order to continue his conquest he needed more and more money, and so he had his government in England ruthlessly demand more taxes from the nobility, who were simply expected to pay tax whenever the king asked.

Indeed, as king, John was entitled to many customary payments from his tenants in chief:

“He could demand money on the marriage of his eldest daughter or when his tenants’ heirs inherited their estates; he had the lucrative right of wardship over tenants’ heirs who were minors, and he could control the marriage of his tenants’ widows and heirs. The barons also owed the king a payment called ‘scutage’ in place of military service.”

The ‘scutage’ tax was the focus of much baronial discontent. In 1214, the French defeated a mercenary army that had been raised by King John at the Battle of Bouvines in the north of France. This army had been funded by the ‘scutage’ tax, and these barons very soon became unhappy with the way that King John was exploiting their loyalty and faith in the king’s complete power.

The barons urged that John should agree to confirm the coronation charter issued by his ancestor King Henry I in 1100. This charter promised to “abolish all the evil customs by which the kingdom of England has been unjustly oppressed.”

But King John refused to meet the demands of the barons. In 1215 the dispute escalated resulting in many of the barons renouncing their oaths of allegiance to the king, naming the noble Robert Fitzwalter as their new leader.

Under Fitzwalter, the barons rebelled, and captured the city of London, forcing King John to negotiate. The two sides of the dispute met at Runnymede, near Windsor on the River Thames in June of the same year. Here, the barons’ demands were recorded in a document that became known as the Articles of the Barons. In response, King John granted the Charter of Liberties – or the Magna Carta, as it has since been known – on June 15 1215. Four days later, the rebel barons made their formal peace with the king once more, and officially renewed their oaths of allegiance to him.

The 25 Barons of Magna Carta

The barons, of course, were not fools. They knew very well that there was a risk that, once King John had departed Runnymede, he would simply renege on the Magna Carta. And so they came up with a solution to militate this event in the famous 61st clause of the document – the security clause.

This is the clause where the king concedes that,

“the barons shall choose any twenty-five barons of the realm as they wish, who with all their might are to observe, maintain and cause to be observed the peace and liberties which we have granted”.

Any infringement of the charter’s terms by the king or his officials was to be notified to any four of the committee; and, if within forty days no remedy or redress had been offered, then the king was to empower the full committee to “distrain and distress us in every way they can, namely by seizing castles, lands and possessions” until he made amends.

The names of the 25 barons are not actually listed on the charter. However, the composition of the committee is in fact known from the list that was later given by Matthew Paris, the celebrated chronicler of St. Albans Abbey.

Their names:

- Eustace de Vesci

- Robert de Ros

- Richard de Percy

- William de Mowbray

- Roger de Montbegon

- John FitzRobert

- William de Forz

- John de Lacy

- Saer de Quincy, Earl of Winchester

- Richard de Montfichet

- William de Huntingfield

- Roger Bigod and Hugh Bigod

- Robert de Vere

- Geoffrey de Mandeville

- Henry de Bohun

- Richard de Clare and Gilbert de Clare

- William D’Albini

- Robert Fitzwalter

- William Hardel

- William de Lanvallei

- William Malet

- William Marshall II

- Geoffrey de Say

These were the men that were seen to be the enforcers of Magna Carta. Their role, indeed, was military in nature, and it should be noted that they did not immediately surrender the city of London as soon as the document was signed.

Magna Carta – An Immediate Success…?

No. Not in the slightest.

Yes, King John agreed to the terms of Magna Carta, and yes, the barons renewed their oaths of allegiance to him. But the settlement did not last long. The security clause and the 25 barons of Magna Carta made it difficult for King John to wriggle out of the agreement as freely as he would have liked (for he had now given the royal seal of approval to a document that made him as susceptible to the law as any other ‘free man’), and he was much aggrieved by the manner in which Magna Carta had been enforced. And so he sought help from the Pope

Pope Innocent III

At the time, the pope was the official overlord of the kingdoms of England and Ireland. King John sent messengers to the Pope requesting that Magna Carta be annulled. In response, the barons did not give up the city of London, and vowed not to do so until the terms of the charter were implemented.

Pope Innocent III saw the Magna Carta from the king’s perspective, however, and was indeed very alarmed by the charter’s terms. On 24th August 1215 the pope issued the papal bull, a document in which he describes Magna Carta as “illegal, unjust, harmful to royal rights and shameful to the English people”. The papal bull declared Magna Carta “null and void of all validity for ever”.

Civil War

September 1215 saw civil war break out between the barons and King John. The King was able to raise a mercenary army to fight his cause, and the barons once more renounced their oaths of allegiance to him. Indeed, they invited the King of France’s son, Prince Louis to accept the English crown.

Louis invaded England the following year, and the country was still at war when, on the night of 18th October 1216, King John died of dysentery.

John’s son thus acceded to the English throne when he was just a 9-year-old boy. At this point, the Magna Carta was effectively dead – but it wasn’t long before the young king breathed a new lease of life into the document.

In November 1216, a revised version of Magna Carta was issued in King Henry’s name, with the purpose to regain the support of the barons. A further version of the charter was granted in 1217, once the French army had been expelled from English soil.

But it wasn’t until 1225, when the king had turned 18, that Magna Carta underwent a further, much heavier revision, the result of which produced the definitive version of the document, which was later enrolled on the statute book by King Edward I in 1297.

Magna Carta: Long Term Legacy

The true success of Magna Carta is found in its long-term legacy, rather than what it achieved immediately following its initial penning. Although it is largely regarded as being the foundation of democracy in England, most of the document’s initial terms applied only to a small proportion of the 1215 population.

Indeed, more than one third of the charter’s 63 clauses in the original 1215 Magna Carta dealt directly with feudal rights, which King John had theretofore repeatedly breached the bounds of traditional practice.

In addition, King John also regularly abused the justice system to suppress his opponents and extort revenue from the barons. Notions of justice, therefore, were the second main theme of the document’s clauses, of which the barons ensured that the details were defined as to how the justice system and its officials were supposed to operate.

The king was also supposed to return all hostages that he had taken, to remove all foreign mercenaries and knights from England, to remit all fines that had been unjustly exacted, and to restore lands, castles and liberties to all that had been wrongfully deprived of them.

Most of these clauses, of course, were of and pertaining to the time, and so it is hardly a fair assessment to bestow the whole basis of English democracy on this now far outdated document.

However, there are 3 clauses that do remain in English law to this day, the most famous being:

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

3 Facts You May Not Know About the Magna Carta

It’s not certain who wrote it

The closing line of the document suggests that the charter was “Given by [John’s] hand”. But, due the fact that Magna Carta was forced upon him by his barons, this seems unlikely. 19th Century historians believed that the document was in fact penned by one of its most influential signers – Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton. The exact wording of Magna Carta, however, would have been the product of a lot of negotiation between the king and his barons.

There’s No Single Original Copy

Multiple copies of the original 1215 Magna Carta were produced and distributed to individual English count courts upon the document’s initial creation. Of these, 4 still survive – 2 can be found in the British Library, and the other 2 are in the collections of the cathedrals at Salisbury and Lincoln.

There are a handful of other revised Magna Carta versions that were penned between 1225 and 1297 in existence. In 2007, a Magna Carta dating 1297 sold at auction for $21.3 million, the largest amount ever paid for a single piece of text.

Magna Carta Was Not Actually the First of Its Kind

The Magna Carta has gained historical significance for being the foundation of English democracy. However, the Magna Carta itself was based on previous charters by previous rulers. In 1100, King Henry I issued a 20-clause coronation charter, in which he promised to rule justly, off the church greater financial freedom, and reduce royal meddling in the family inheritances and marriages of his barons.

Much like King John, however, Henry kept few of his promises, though it was this coronation charter that formed the basis for the Magna Carta in 1215.

Magna Carta Today

Today, the Magna Carta enjoys a special status as being the cornerstone of British liberties, and indeed in the liberties of various nations around the globe – not least in the United States.

Despite the fact that 60 of the original 63 clauses are now no longer in existence in English law, and that the document itself has long been superseded by other legislation (such as the 1998 Human Rights Act), it is in the spirit of the document as both a guarantor of individual liberty and defence against tyrannical rule that the Magna Carta survives in the collective sub-conscious of all who live in the free world today.

Magna Carta Conservation Treatment

Magna Carta – Lecture by Prof. Linda Colley (BBC)

Magna Carta’s Legal Legacy: Conversation with Chief Justice Roberts & Lord Judge

Further reading: The Magna Carta 800th Anniversary